How to bend the curve of luck

You too can take advantage of the asymmetry of adaptivenessOriginally published via Substack, May 09, 2025. Hello!

OK now let’s get to bending the curve of luck. A few years ago I was leading a product team at a US-based recruitment-tech startup. We were on a tight deadline to build something that depended on a third-party API we’d never used before. It was a situation I’d been bitten by umpteen times in the past, and a creeping sense of deja-vu whispered to me that we had to resist the (totally understandable) urge to press ahead without “wasting” a single second. Instead of jumping straight into design mockups, we made a quick Multiverse Map with the team. It took just half an hour, and it immediately surfaced the biggest unknown … would the API actually be able to do the list of stuff we expected? One of the engineers took it upon himself to investigate. Within an hour, he came back: “The documentation is totally wrong. Here’s what it actually does …” That realisation meant we had to rethink the whole experience. This would’ve happened sooner or much (much) later. But because we hadn’t sunk loads of effort into designing any high-fidelity screens, there was nothing painful to throw away. We just rejigged the map and kept running. It was a matter of minutes to pivot, and we hit the deadline without even a tickle of panic. “Build, measure, learn” is the cry of the startup crew. Twenty years ago I was no different. Problem is – it takes too long to get signals back from the real world. And there’s always far too much building before there’s any measuring, let alone learning. A more accurate mantra would be “build, build, build”. At the other end of the spectrum, “learn first by doing research” is its own can of worms. Even in organisations where research is considered (which are rarer than a stain-free toddler t-shirt) everyone is under pressure to deliver answers that people want to hear. Research that finds inconvenient truths often gets deflected, undermined or explained away. Evidence mostly doesn’t change minds. (If you’re lucky enough to be in an organisation that hires skilled researchers, allows them to do a great job, and actually listens to what they say, then are you hiring? Let us know where to send people!) But in the majority of tech organisations at least, the dominant pressure is to build. And so build is what most people working there have to do. While I was still working with the recruitment-tech startup, the team was convinced that building a Calendly integration for recruiters was an absolute no-brainer. The data supported the need for the idea and leadership loved it. Engineering estimated a few months of work to nail the integration. Again, we paused to make a quick Multiverse Map. Within 40 minutes, it was obvious that we were sitting on a huge behavioural uncertainty: we couldn’t confidently say how (or even whether) customers would use this integration. Instead of going round in circles debating, we wrote a short email to ten of their customers offering that we’d do the legwork to set them up with full Calendly accounts for free. The team were pretty confident that all ten would say yes to such a generous offer, so we set a simple pivot trigger: if at least six out of ten said yes, we’d work with them to build the integration. If we didn’t meet that threshold, we’d think again. Can you guess how many people actually said yes? None at all. In only a week, with barely any effort, we dodged many months of wasted work. The engineers could now focus on something that customers actually valued. Multiverse Mapping (free intro course here) isn’t a magic bullet. It won’t solve all your problems, give you easy answers, or bend people to your will. But it will lead to shared understanding, strategic alignment and richer conversations. At its core, this is about antifragile prioritisationAntifragility means something or someone becomes stronger when exposed to uncertainty, risk, or stressors. For teams and leaders, I reframe it slightly. Antifragile prioritisation means this: Your project grows more likely to succeed when you prioritise getting signals from your areas of greatest uncertainty. This tends to introduce a gnarly Catch-22: you most need to learn about the things no one knows how to ask about. Useful up-front research needs clear, well-defined questions, but your areas of greatest uncertainty are often places where no one even knows what questions to ask. This makes them feel ambiguous, even scary. They’re frequently organisational blind spots, where people are wary about asking questions in the first place. So the parts of the project plan you most need to explore — the parts with the biggest risk and the most generative power — are also the parts you’re least equipped to tackle using traditional methods. That’s why you need to build, measure, learn at the same time. In practice, this is surprisingly easy. It typically means you do the exact same work you were going to do all along – you just do it in a different order. Here’s what I’ve seen work:

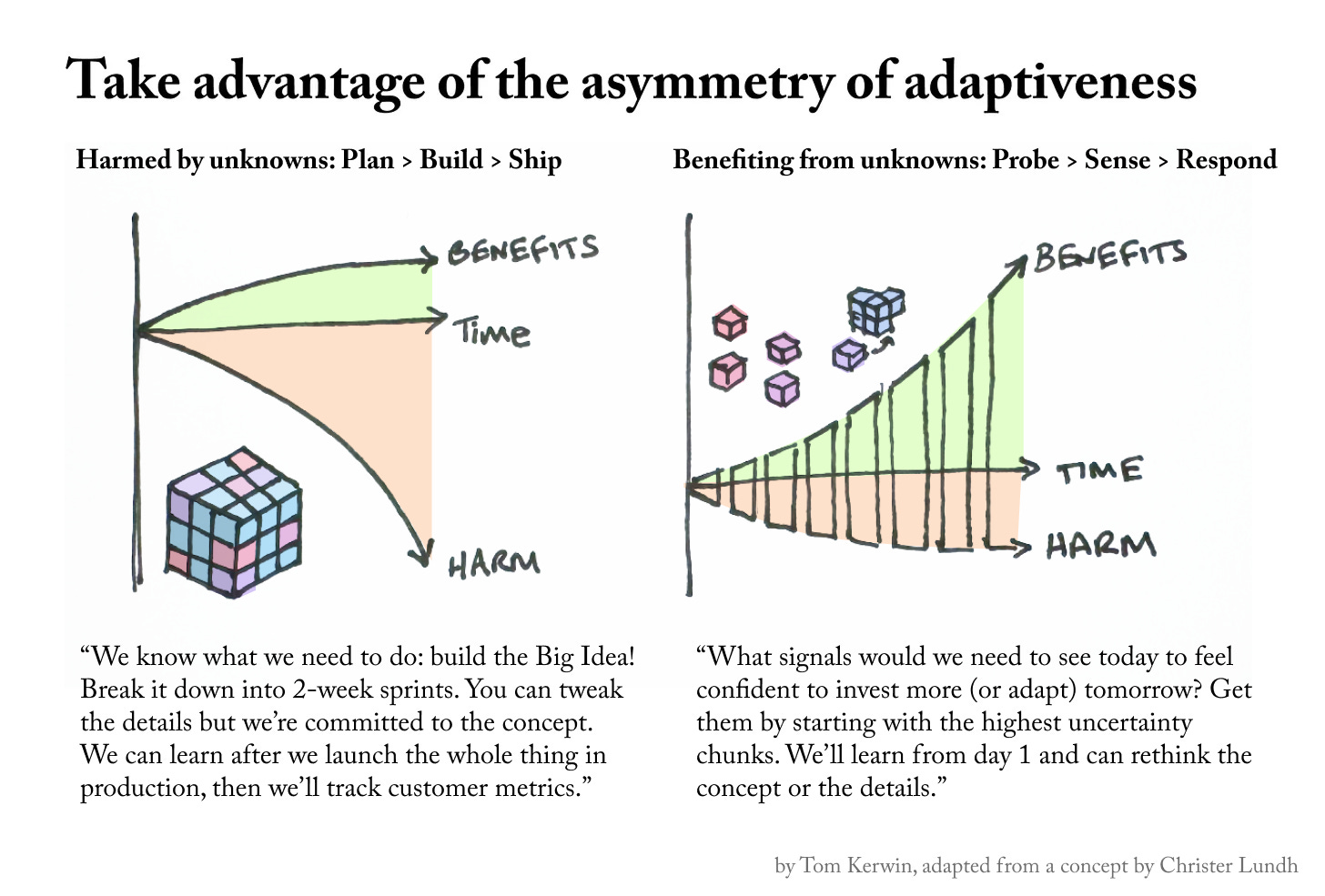

The asymmetry of adaptiveness: bending the curve of luckImagine a project that reaches the point of being 90% done and then you find out that an API doesn’t do what you expected. Or an analyst stumbles across a hidden hurdle. Or that customers rebuff your offer. Oh wait, you probably don’t need to imagine this, because it’s exactly what happens on many projects. If you can unearth major disasters in the first few days, you’ve got plenty of time to adapt. And you haven’t already made a load of decisions that painted you into a corner. The kind of signals you collect this way are also real and relevant to your specific project and context, so they cut through – they’re hard to deflect, undermine or explain away. By tackling the biggest-uncertainty type work first, you buy yourself the luxury of having plenty of time to adapt if the uncertainty turns out to contain nasty surprises – or if the uncertainty turns out to contain an even better idea than you started with. Here’s how antifragile prioritisation — and benefiting from unknowns rather than being blown up by them — can bend the curve of luck in your favour:

I’m speculating here, but my sense is that the approach I’m recommending works because we humans are wired to hate uncertainty but at the same time we love closing loops. First we’ll try to avoid the uncertainty, but once we’re forced to acknowledge it, we have an irresistible itch to go and tackle it and get answers. This explains why you can’t just say “hey team, let’s go tackle the uncertainty!”. There’s way too much of it to tackle, and the vast majority of it won’t have a direct impact on any given project. Where would you even start? Instead, you need to way to chunk the vast fog of uncertainty into relevant, bite-sized puzzles your team feel they can manage.

“The best effect is that it handles granularity without thinking about it. The energy that followed of wanting to take action within the different groups was really nice to see. Multiverse Mapping is a good tool to have in the toolbox.” – Johan Sjöström, CEO Multiverse Mapping is the best way I’ve found to help teams surface, label and act on manageable chunks of uncertainty. And that’s how you bend the curve of luck. Give it a try. I’d love to hear how you get on with it. (Here’s that link to register for Monday’s free event, Intro to Multiverse Mapping. If there are no spots left by the time you read this, don’t worry: I’ll be running more in coming months.) Tom & Corissa x P.S. In the full course I walk you through all my best tips and tricks for making maps with teams, along with the big mistakes to avoid. And there’s a whole hour of material on how to prioritise work and design quick probes to get you those signals that cut through the noise. With thanks to Christer Lundh for the original diagram of the curves of luck, to Matti Heino for correcting the graph so it’s showing convexity correctly, Nassim Nicholas Taleb for popularising antifragility, and the many teams who’ve helped me shape Multiverse Mapping. |